Injuries happen. Planned or unplanned surgery might put us in bed for a while. Do you really need that brace? What are the consequences of as little as two weeks in a brace? Did you sprain your ankle and require a boot for a few weeks?

What happens to our bodies when we are inactive— even for a short period of time? Leading a sedentary lifestyle is the norm for most people. Therefore most people are already starting with marginal muscle mass and the complex metabolic consequences of a sedentary lifestyle.

What are the metabolic, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal effects of inactivity associated with injury, casting, or recovery after surgery? We are highly complex beings. I guarantee this topic will be of interest if you are recovering from an injury, or if you are planning on having surgery in the near future.

Do we recover quickly from these periods of rest? Are there ways to limit the downsides of forced rest or ways to improve our recovery for a planned surgery?

How much activity do we actually need?

While the WHO recommends that we achieve 120 minutes of aerobic exercise each week, there has been some research that shows significant benefits to our health with walking as little as 5,000 steps a day. More recently, some research groups have shown that just walking around the office or parking lot each day, or parking further away so you walk a little bit more than normal can also have health benefits.

We have always heard that we should be more active and exercise more… but why? We are a highly complex system. Do you know what happens within your body when you have a period of inactivity or bed rest? Do you know what happens and which systems in your body during recovery from surgery or an injury? It might surprise you. Many physicians feel that having these complex discussions with our patients isn’t necessary.

This Orthopedic Surgeon feels quite the opposite. In my experience, if I explain what the effects of inactivity and increased activity are on your body then I often get people to start exercising more often… or at the very least I get them to make their day a little harder.

Health consequences of inactivity or bed rest

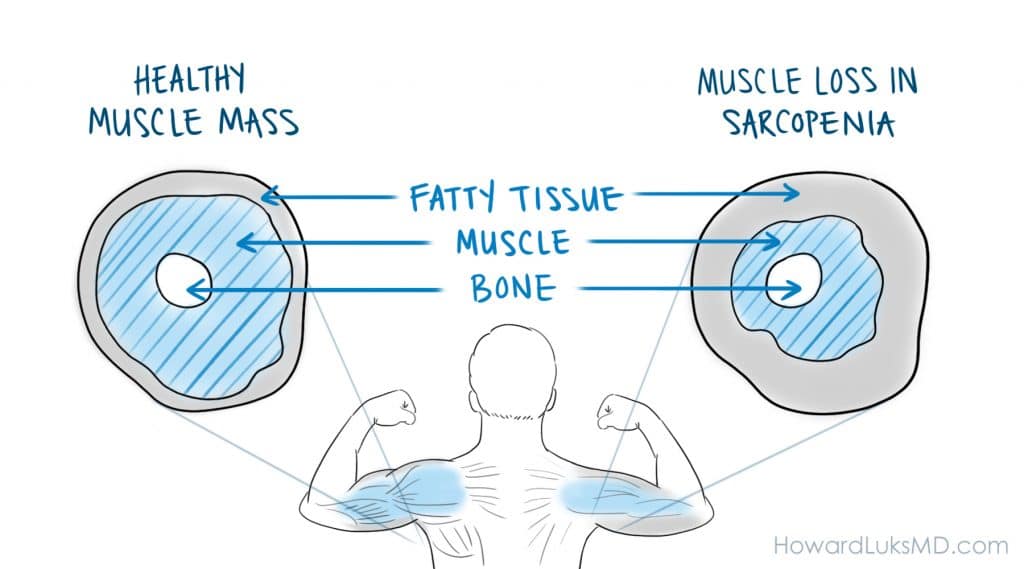

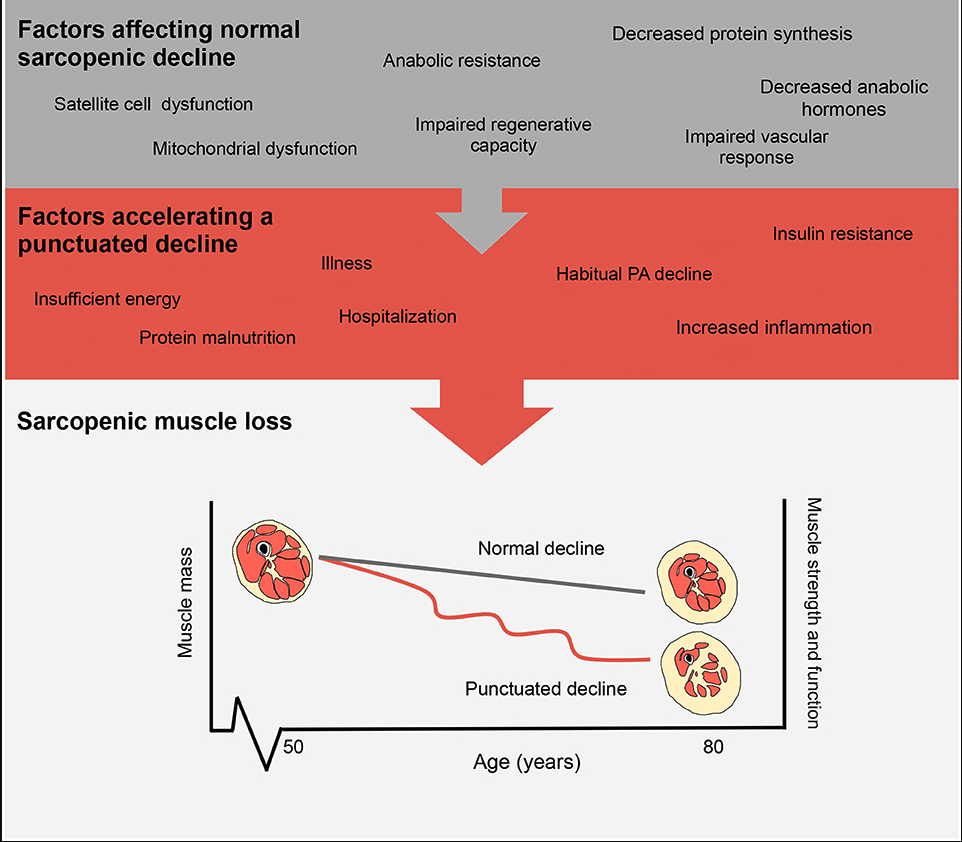

Inactivity alone sets us up for sarcopenia or age-related muscle loss. Beginning in our 40s we start to lose as much as 1% of our muscle mass and 3% of our muscle strength per year. This can be compounded by forced periods of rest due to injuries or recovery due to elective surgery. Aside from the loss of muscle mass, the metabolic consequences can be just as severe.

Episodic complete muscle disuse can be due to sickness-related bed rest or disuse of a single limb due to immobilization or surgery. Alternatively, relative muscle disuse occurs during inactivity due to illness and the associated convalescence resulting in marked reductions in daily activity.

The physiological consequences of even short-term inactivity show losses in muscle mass and strength, as well as impaired insulin sensitivity and an increase in systemic inflammation. Though seemingly benign in comparison to bed rest, periodic inactivity occurs with advancing age due to illness, declining mental health, and declining mobility.

Even in our 20’s and 30’s we suffer from many of the same consequences as our parents and grandparents. Younger generations may recover faster, but proper preparation can improve the time course of recovery, and the completeness of recovery.

Inactivity, whether forced upon us or due to our lifestyle has an impact on our health and wellbeing. The consequences to our health from a period of forced rest or recovery will vary based upon the fitness level we had at the time our recovery period began.

Just two weeks in a cast in young men led to a reported reduction in quadriceps muscle volume, and strength by 9 and 23%, respectively. Two weeks! Most casts are on for 6 weeks or more. Even though braces are not needed following ACL surgery, many people still get them. If you are in a brace for two weeks without PT or exercise you lose at least 25% of your strength!

Many of us start off from a position of weakness

Sedentary lifestyles, as you will read further down the page are very unhealthy for us. But what happens if you have an injury, are forced to rest more than usual, or need to recover from surgery? How long do those effects last? How can you minimize the side effects of immobilization and recovery from injury?

Sarcopenia is the term we use to describe the muscle loss that is associated with aging. Sarcopenia will contribute to a number of health issues such as an increased risk of falls, broken bones, and reduced mobility. The process of sarcopenia begins in our 40’s. The process ramps up in our 60’s. By then you are losing 1% of your muscle mass- or the volume of your muscle tissue each year. In addition, you are losing approximately 3% of your muscle strength each year! Those should be alarming numbers in and of themselves. Because of this, we had a recent post that discussed why leg exercises are so important to support healthy aging.

Muscle metabolism is important:

Our muscle and our fat stores are two highly metabolic and important tissues. Our muscles help regulate our glucose levels. In 2019, about ⅓ of people are obese and around the same number are at risk for type diabetes. Hyperinsulinemia precedes the emergence of type 2 diabetes by a few years. You should know your fasting insulin levels more so than your A1c levels.

Your muscles use glucose as energy. Your muscles store glucose in the form of glycogen. Only your liver and muscles can store glycogen. The larger your muscles, the more glucose you burn for energy. The larger your muscles the more glycogen you have and the less glucose you have that can circulate around your body.

Excess circulating glucose is the root cause of hyperinsulinemia and type 2 diabetes. It is a common cause of chronic systemic inflammation (CSI). CSI is one of the root causes of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, dementia, arthritis, tendon related problems and so much more. Any loss of muscle due to inactivity or forced rest due to recovery will increase your risk of developing hyperinsulinemia and the chronic disease burden associated with elevated glucose and insulin levels.

Researchers have observed elevated levels of TNF- α and CRP (inflammatory mediators) in response to inactivity in non-diabetic, normal-weight patients. Other researchers found an increase in levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP following inactivity in overweight and obese pre-diabetic participants. These inflammatory mediators can take many weeks to return to normal levels even after your recovery has started.

Your abdominal fat is not your friend. Visceral fat is the name given to the fat in our belly. In wraps around our organs internally. Visceral fat is also highly metabolic. But unlike our muscle, the results of metabolic activity of visceral fat will increase our risk of developing a fatty liver- NAFLD, CSI, and many other chronic disease states. In an optimal state, we have little or no visceral fat and limit its access to circulating glucose to limit the growth of visceral fat.

When we are forced to recover from an injury, or we are sedentary, excess glucose and excess insulin can increase our visceral fat mass which in turn increases our risk of developing diseases we would rather not have.

This becomes a vicious cycle. An increase in insulin resistance causes an increase in reactive oxygen species and many other changes to the master nutrient sensor that is mTor which causes a decrease in muscle protein synthesis. If you make less muscle, you will develop muscle loss or muscle atrophy. Again… we are highly complex beings. See this paper for a nice deep discussion on these complex interactions.

Injuries Happen … What happens to our bodies during the recovery process?

Now, all of us will be injured or sidelined at one or many times in our adult life. Our level of activity will drop, we might be forced to stay in bed, and the recovery process may be long— as it is following some knee replacements.

What are the consequences of these periods of lesser activity if we are already suffering from sarcopenia and we start off in a position of poor metabolic health?

Even short term periods of decreased activity can have dramatic effects on our overall health. Smaller muscles and loss of strength will affect many different systems in our body. Poor glucose regulation can affect healing, risk of infections and the risk of other chronic disease conditions.

Muscle tissue is highly metabolic. That means that it is a very active tissue. Muscle is constantly burning glucose and fatty acids for food. Muscles, therefore, contribute significantly to our overall glucose management. Glucose is very important. Our body maintains our glucose levels in a very tight range. Too much glucose, as in the various forms of diabetes can have life-threatening effects on our body. Insulin helps maintain glucose levels. A very significant percentage of our population has something called hyperinsulinemia, which means that they have too much insulin in their blood. That occurs due to a process called insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance is present in an alarming number of people. Insulin resistance means that your body will require more insulin to have the same glucose-lowering effect as someone without insulin resistance. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia will often precede the development of type 2 diabetes by a few years. Therefore, it is important to understand how you can combat this issue to decrease the associated chronic disease burden.

In addition to the loss of glucose regulation, we will not be disposing of or using up the glucose in our blood. Therefore more glucose will be flowing through our body. Our liver will not allow that to happen for long. Our fat cells will also respond. We have different types of fat cells in our body. The subcutaneous fat under our skin is relatively quiet from a metabolic perspective.

But belly fat or visceral fat is also a highly metabolic tissue. In addition, belly fat produces many inflammatory mediators or chemicals that are harmful to us. If the visceral fat sees a rise in the amount of glucose and fatty acids in our blood– because our muscles are less active– then the visceral fat will store that “energy” and become larger. That will potentiate the ill-effects of your visceral fat burden.

As I mentioned, our muscles are metabolically active tissues, therefore the more muscle mass we have, the more glucose we are disposing of. Muscle mass helps regulate insulin resistance. The more muscle mass we have, the less likely we are to have insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Now you can see what happens if we have sarcopenia and an even greater drop in muscle mass associated with immobilization or convalescence.

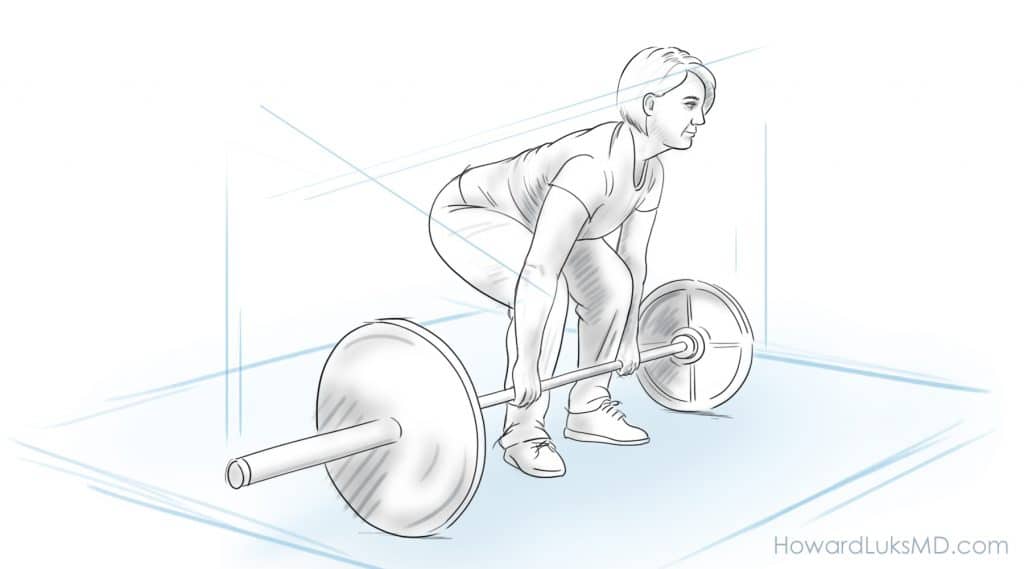

When we are in a cast or splint our muscles become much smaller, or atrophy. The same happens if we are forced into bed rest by illness, injury, or surgery. Our muscle mass loss increases dramatically. It is estimated that we lose 20 % of quadriceps muscle volume by laying in bed for as little as two weeks.

Cardiovascular, Metabolic and Muscle changes associated with increased activity

An increase in activity, whether aerobic or resistance exercise can stimulate our muscles to grow and become more active. How does exercise of activity do that?

Nearly all our cells have mitochondria. A mitochondrion is an energy factory. It takes in energy sources such as glucose and spits out ATP which our muscles and tissues use to power our muscle cells and a multitude of other important chemical reactions in our body.

Our bodies are very efficient systems. We will not have more mitochondrion than we need. That’s one of the reasons why your muscles get tired or sore from a little extra work. As we push our muscles further, the muscle cells will respond by increasing the number of mitochondria in each cell. The more mitochondria we have, the more glucose we burn, and the more energy we have.

In addition, our mitochondrion becomes more efficient at burning fuel as we become more active. That allows us to exercise longer or harder without getting exhausted or sore.

Insulin resistance: During a period of mechanical unloading, or rest, insulin resistance increases. As mentioned previously, this leads to many downstream effects that lead muscles to decrease new muscle protein synthesis. Our muscle protein is in a constant state of turnover.

Following a period of just two weeks of step reduction, the fasted plasma glucose and insulin levels were significantly elevated following by 8 and 31%, respectively. Fasting glucose and insulin levels did not return to pre-injury levels following a two-week recovery. So even after your recovery begins, you are still suffering from the metabolic consequences of inactivity.

We are constantly breaking down muscle protein and synthesizing new muscle protein. If there is an imbalance in that system, muscle atrophy or loss of muscle mass will occur. For those who love physiology details, it appears that a decrease in IGF-1 signaling and an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) worsens insulin resistance. Downstream this effects mTor and other pathways which ultimately leads to a decrease in muscle protein synthesis.

Muscle atrophy: Loss of muscle mass is referred to as atrophy. Think of a skinny leg that just came out of a cast. Muscle atrophy occurs for many reasons. The first and easiest to understand is that an immobilized muscle is not under tension and is not doing much. Therefore the muscle will lose its bulk.

We tend to lose our Type 1 fibers (slow-twitch) muscle faster than Type 2 or fast-twitch muscle fibers. Next, as we just discussed, there are numerous physiological changes that take place. That leads to an increase in CSI, which ultimately affects nutrient-sensing pathways (mTor, etc) which leads to a decrease in muscle protein synthesis. This compounds the issue of decreased load on the muscle and leads to a further decrease in muscle volume or mass.

Muscle size or volume: A decrease in muscle mass occurs due to muscle atrophy. This will cause weakness, loss of endurance and loss of mobility. As we discussed elsewhere on this website, a decrease in muscle mass and strength has significant impacts on our health.

Do you have questions regarding an Orthopedic injury or longevity?

Do you want to talk to an expert who can listen to you for 45-60 minutes and explain the options in detail?

Dr. Howard Luks offers remote guidance sessions to review your X-ray or MRI images and explain your options.

Dr. Luks has also received hundreds of requests for educational sessions on the topics discussed in his book, Longevity Simplified.

Twice a year I seem to get horrible spasms in my lower back. That makes moving around very challenging. My only saving grace is that I have been performing pretty intense leg exercises for years. Those strong legs become very useful when my low back is not cooperating with my desire to move. If I did not have the leg strength that I have, getting up from a chair, couch or the floor might be impossible without someone else’s assistance.

Plan for an eventual recovery from injury or illness:

Everyone is going to be sidelined. Some of us may need an unplanned surgery. Being physically fit, and metabolically fit is critical if you want to recover quickly and limit the awful consequences that immobilization has on your health.

Starting now is the best time to start :-).

Make Your Day A Little Harder…

Exercise is very hard for some of us. It comes naturally to others. I have worked with thousands of you over the years. I have seen many of you become just as addicted to exercise as I am. At first it is work… no doubt. But stick with it, and you may just like it, or at least you will like how you feel.

Making your day a little harder is a neat little concept. It adds activity to your daily grind without you having to commit to going to a gym, or to walk in a park, etc.

- Don’t park in the spot closest to your building. Park as far away from the office, supermarket or mall entrance as possible.

- Don’t sit in your car on your phone at work in the morning… If you get to work a little early, even just 5 minutes, take two laps around the parking lot. I see you in your cars every morning polluting the world as your car runs while sitting idle. Get out, get moving. 5 minutes, two laps… you can do that!

- Do not let yourself take the elevator too often. If you are going up 2 flights or less, take the stairs. If you are going down 3-4 flights, take the stairs.

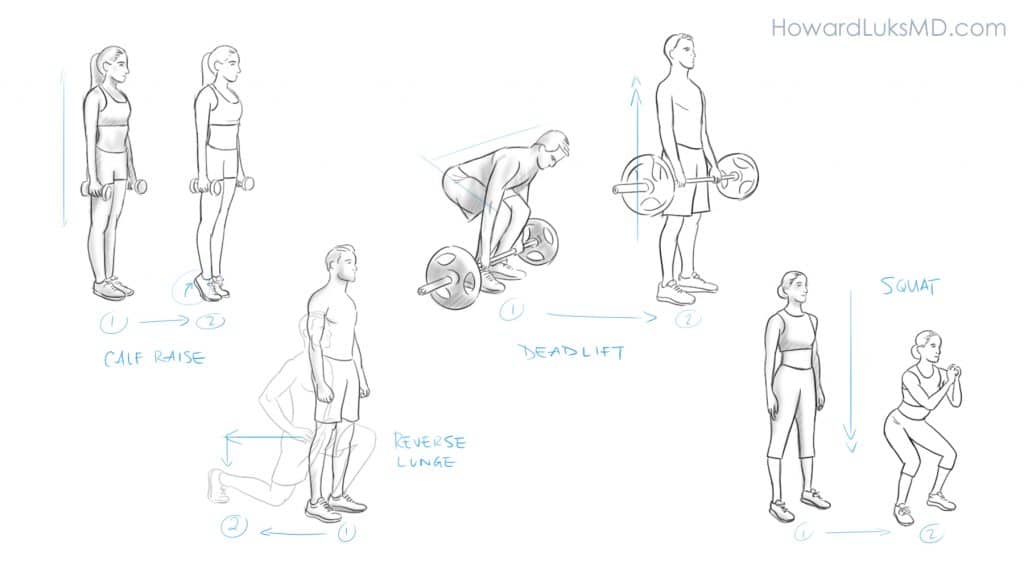

- Before sitting down after getting back to your desk, do 5 calf raises. Just hold onto the back of your chair and push yourself up onto your toes.

- Drop something on the floor? Squat down 3 times before you pick it up. Don’t kneel down to get it.

- Don’t race to your car after work. Leave your building through an exit on the other side of the building and walk to your car. These added steps add up rapidly.

- Make up your own “Make Your Day Harder” routine and share it with us in the comment section below!

Improve your recovery. Prepare, Plan, Exercise, and Supplement

Be active.

Even short walks each day have important effects on your recovery. Lying in bed all day can potentiate the downstream effects of immobilization and add weeks to your recovery. Talk to your doctor. If you are allowed out of bed, get out of bed. Have someone assist you and walk.

Resistance exercise during recovery.

Exercising a non-injured arm or leg affects the muscles of the injured arm or leg. Crazy, right? As I mentioned earlier, we are highly complex beings. So if your doctor tells you it’s ok to go to the gym or do resistance exercise on the non-injured side go ahead. Resistance exercise on the non-injured limb still improves your glucose metabolism, improves your cardiovascular system, and releases chemicals that affect the muscles in the recovering limb.

We have several “nutrient-sensing pathways” in our bodies. We have major signaling hormones and chemicals. IGF-1 is but one of them. mTOR is another. By exercising the non-injured limbs, preferably the leg because it has larger muscles, you will trigger these pathways in such a way that it favors muscle protein synthesis. That can mitigate the further loss of muscle in the injured limb. This paper goes into significant detail about these mechanisms if you wish to dive deeper.

Anti-Oxidant use during recovery.

Reactive oxygen species are oxidants. They have a role in signaling that leads to muscle atrophy. Many different anti-oxidants have been studied to try and decrease the muscle atrphy that occurs with recovery or inactivity. Researchers have studied fish oils, curcumin, Vitamin E, and polyphenols such as resveratrol. It appears that some of these may have beneficial effects.

Fish oils and resveratrol are reasonably safe and with reasonable doses do not have known significant side effects. Fish oils at a dose of 3-5 grams per day have been shown to decrease muscle mass loss and improve muscle protein synthesis.

You can discuss whether or not you should take them with your surgeon or primary care doctor.

Nutritional needs during recovery:

In order to maintain a proper level of muscle protein synthesis, your body requires protein. Of all the amino acids that your proteins are made of, Leucine appears to be the most important. Leucine is a potent modulator of mTor which stimulates muscle protein synthesis. During recovery or bedrest total daily protein intake of 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight is suggested. Alternatively, 5 grams of Leucine combined with 6 grams of whey protein can be used as a supplement at mealtime. Again, talk with your surgeon or doctor about a nutritional protocol to minimize the risk of muscle loss.

Dr. Stuart Philips writes a lot about this topic. One recent article may be of interest if you would like to read more on the topic of protein needs to offset muscle loss during recovery.

Preparing for elective surgery.

Even if you are 80, you are still capable of building muscle mass and muscle strength. As little as 8-12 weeks of training can improve both your muscle size and strength. You should talk to your doctor about pre-habilitation. Pre-habilitation is physical therapy before surgery. Every moment you spend exercising prior to your planned surgery will improve your ability to recover after your surgery.