Trail running has long been my happy place. Actually, any form of running enables me to start my day invigorated and ready to go. Regular exercise associates with many upsides. Exercising so that we can live longer is a draw for a few. Most master athletes I have met exercise because they have to. They thrive on the hormone rush that follows, they thrive on the brain clearing effects of a walk/run through the trees.

Mary was a 76 woman I met at the starting line a few months ago. She’s been running for decades. She loved to run for many different reasons, but she was finding it increasingly more challenging to finish a course in the allotted time. She had no intention of stopping and was very interested in meeting in my office one day to address strategies to help her maintain her running habits deep into her elder years.

Over the last two decades of treating athletes of all ages, it has become apparent that older athletes are just as driven as my younger superstars. They thrive on the thrill of a race, regardless of pace. They thrive on the way it makes them feel, and they will go to any length to protect their time on the road or the trail.

Physiological changes associated with aging

Aging is a natural process that brings about physiological changes in the body. These changes can affect physical capabilities and performance, particularly in athletes. Understanding these changes is crucial for adapting lifestyle and exercise routines to maintain health and functionality.

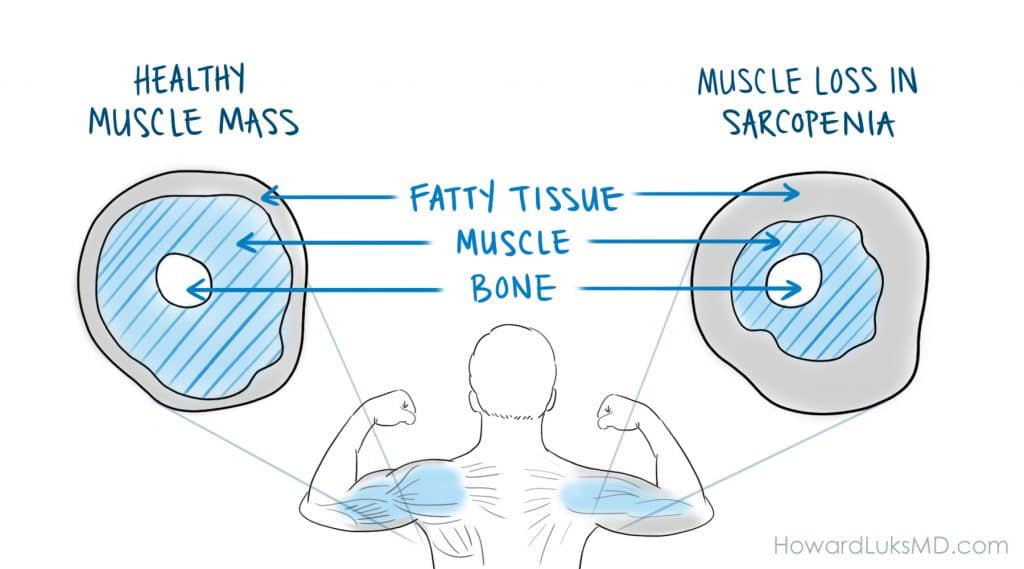

1. Muscle Mass and Strength (Sarcopenia): As individuals age, they often experience a gradual loss of muscle mass and strength, a condition known as sarcopenia. This decline can start as early as the 30s and accelerates with age. Sarcopenia can affect balance, gait, and overall physical performance.

2. Bone Density (Osteopenia and Osteoporosis): Aging is associated with a decrease in bone density and strength, leading to conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis. This increases the risk of bone stress injuries and fractures as bones become more brittle and less able to withstand stress.

3. Joint Health: The cartilage in joints changes over time, leading to conditions such as osteoarthritis. This can result in joint pain, stiffness, and decreased range of motion, affecting the ability to perform certain exercises or activities.

4. Metabolic Rate: The basal metabolic rate (BMR) tends to decrease with age, meaning the body burns fewer calories at rest. This can lead to increased fat accumulation and make weight management more challenging.

5. Cardiovascular Changes: Aging can affect the cardiovascular system, leading to decreased VO2 max, increased blood pressure, and decreased maximum heart rate. These changes can affect endurance and the intensity at which one can safely exercise.

6. Hormonal Changes: There are significant hormonal changes with age, including decreases in growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen (after menopause). These hormonal changes can impact muscle mass, bone density, and fat distribution.

7. Flexibility and Mobility: Tendons and ligaments become less elastic with age, decreasing flexibility and mobility. This might affect the range of motion and increase the risk of injuries during physical activities.

8. Balance and Coordination: There can be a decline in balance and coordination due to changes in the nervous system and decreased muscle strength. This increases the risk of falls and related injuries.

9. Recovery Time: The body’s ability to recover from physical activities or injuries decreases with age. Older adults may need more time to recover from workouts or injuries than when they were younger.

10. Immune Function: The immune system’s efficacy can decline with age, leading to a longer recovery time and a higher risk of infection.

Understanding these physiological changes is essential for adapting training programs, dietary habits, and lifestyle choices to optimize health and performance in the aging population. It’s about working with the body’s evolving needs rather than against them, ensuring a proactive approach to maintaining fitness and well-being through the years.

Becoming a master athlete

Plainly stated, you have to make it to a certain age to become a master athlete. It sounds cruel, but it is true. A typical Western lifestyle and diet will not likely help you achieve that milestone. You cannot outrun, out-exercise, or medicate away poor lifestyle choices. Your lifestyle choices and decisions around your diet, resistance exercise, balance exercise, and more lay the appropriate foundation for building your master athlete program. Your “metabolic health” matters … your metabolism affects every system in your body… including your muscles, tendons, and joints.

Fad diets are the rage but typically do not lead to sustained lifestyle changes. Eating real food, less of it, and getting enough fiber in your diet to support your gut is clearly advantageous. Despite the banter in certain social circles, monitoring your LDL, homocysteine, uric acid, ALT, insulin, and other basic biomarkers over time gives you a snapshot of how your dietary habits shape your risk for developing chronic disease.

The earlier in life that you focus on your diet and lifestyle, the more likely you are to have the ability to become a master athlete.

The effect of aging on the musculoskeletal system: Sarcopenia

During our more formative years, we laced up and ran outside. We didn’t worry about balance, strength, muscle tone, and energy. As the athlete ages, these become very important issues to address proactively.

Sarcopenia is the process of age-related muscle loss. Starting in our thirties, we start to lose a percentage of our muscle mass each and every year. Muscle mass is critical to performance and has also been proven to predict longevity and a longer health span. Simply put, your healthspan is the number of years that you live relatively disease-free, free of neurocognitive decline and free of a chronic disease burden that threatens your quality of life.

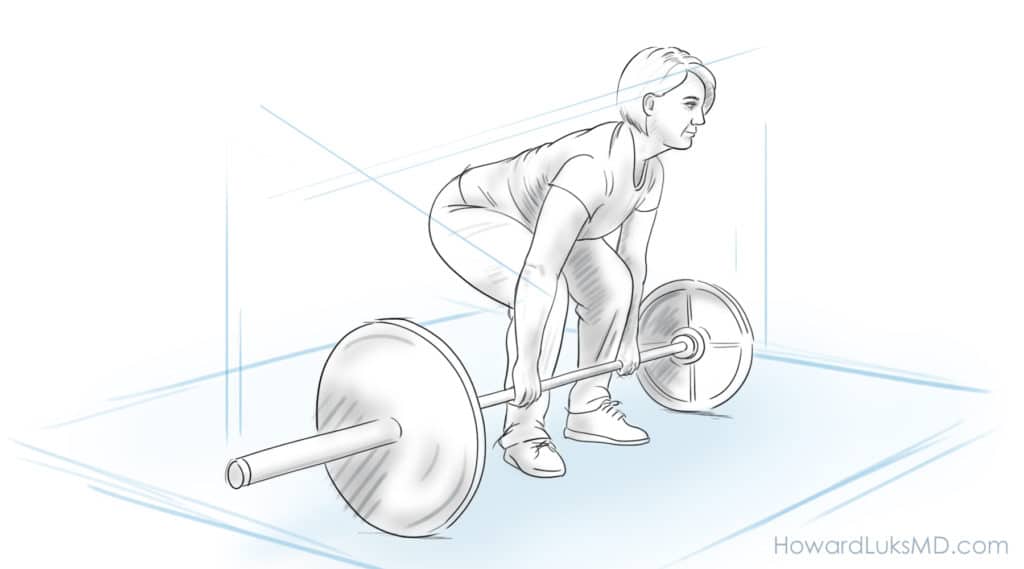

Resistance exercise is a must for the aging athlete. A short, well-balanced program consisting of calf exercises, squats, bridges, biceps curls, and shoulder exercises is critical to lessen the burden of sarcopenic changes and maintain our current muscle mass.

As we age, our body has a harder time making enough protein to suit our needs. Our nutritional requirement for protein increases as we age. Unless you suffer from kidney disease, the average master athlete should be getting a minimum of 1.4-1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. A contemporary body of research shows that the timing of that protein intake isn’t critical. So, you do not need to bring that protein shake with you to the gym or track.

The effects of aging on the musculoskeletal system: Balance.

As we age our ability to balance and stabilize ourselves diminishes. This is a far more serious problem than most people realize. While chronic disease sets us up for a diminished healthspan, injuries sustained as the result of a fall and the downtime to recover from those injuries significantly affect our health and longevity. Diminishing our fall risk starts with an active balance training program. These do not need to be elaborate gym-based programs. This post went into far more detail on the benefits of balance training.

We can perform plenty of balance exercises in the comfort of our home. Standing on one leg for 30 seconds can be challenging enough. When that becomes easy, perturb the system and start to move your arms around while one leg is raised. You will notice an improvement in your balance and control within a few weeks. Switch legs every minute. Carry small cans or 1-pound weights in your hands when body weight alone becomes too easy. You will feel more surefooted and confident after these exercises. Your fall risk will diminish with this program, and you will have diminished the risk of injury after a fall with your resistance exercise program.

Which exercise is best?

Simply put, the best exercise is the one that you will enjoy and continue pursuing because you enjoy it. Different exercises offer different benefits. Research shows that we only need to walk for 15-20 minutes a day to start to see the benefits of exercise. For many of us, that might be enough. For others, it will not be. Many love to swim. Swimming provides an excellent combined aerobic and resistance-based exercise. You will maintain muscle mass, improve your heart function, lower your blood pressure and cholesterol, and improve your glucose management with any aerobic exercise program. Cycling, as well as running, are also great exercise programs. They offer the same benefits as other aerobic exercises, but you must still work on balance and resistance exercises.

“Should I rest?”: Well, Rest Is a Relative Term

“You should rest.” How many times have you heard that? From an orthopedic perspective, the term rest is a relative term. If you are used to running 30 miles/ week and something bothers you, then “rest” might mean running 10-15 miles weekly. If you’re used to running 10-minute miles, you may need to run 12-minute miles. The same goes for resistance training. Absolute rest and ceasing all activities is seldom necessary. You will lose the aerobic or strength benefits of your training very rapidly. After a few weeks of no activity, you are set back months regarding your training level.

The consequences of even a few weeks of inactivity or rest are dramatic. Your body’s chemistry changes, your muscles change, and your heart and lungs decondition significantly.

Understanding recovery is critical.

The concept of recovery is poorly understood. Have you noticed that the day after a particularly long walk, ride or jog your heart rate is a little higher, or perhaps you’re a little short of breath? Your body is telling you that it needs to have a lighter day. Recovery, just like rest, is a relative issue. If you rode your bike 40 miles the day before, then a recovery ride might only be 4 miles. If you jogged 5 miles, then a recovery day might be a 1-mile walk. At least one or two days a week, you should let your body completely rest from resistance or push your aerobic thresholds. That doesn’t mean you can’t hike or take a walk. It simply means that you need to let your heart and muscles recover and repair themselves from your activity over the past week.

Should I insist on an MRI?

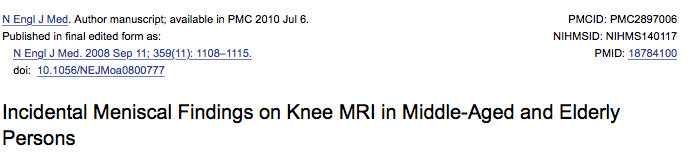

You cannot unsee your MRI report. The answer to this question is almost always no; insisting on an MRI is not always in your best interest. There are certain reasons to obtain an MRI, but it might surprise you to know that those reasons are not encountered often.

As we age, our joints and internal structures, such as the rotator cuff in our shoulder and the meniscus in our knee, will also change with age. Virtually no one over the age of 55 has an MRI of the knee, shoulder, or back that will be interpreted as being “normal.” That means that your MRI will likely show something is “torn,” or, better put- worn out. And in all likelihood, whatever is on your MRI now was there before your knee or shoulder started hurting. It is very hard for many people to grasp this concept.

Hopefully, my radiology colleagues will start to use the term “age-appropriate” change instead of the term degenerative tear. That will lessen the emotional burden of thinking something is torn inside your joints. The research on degenerative meniscus tears in the knee and degenerative rotator cuff tears in the shoulder shows that the vast majority of these will not require surgery. Most people (not all) will respond to a course of physiotherapy.

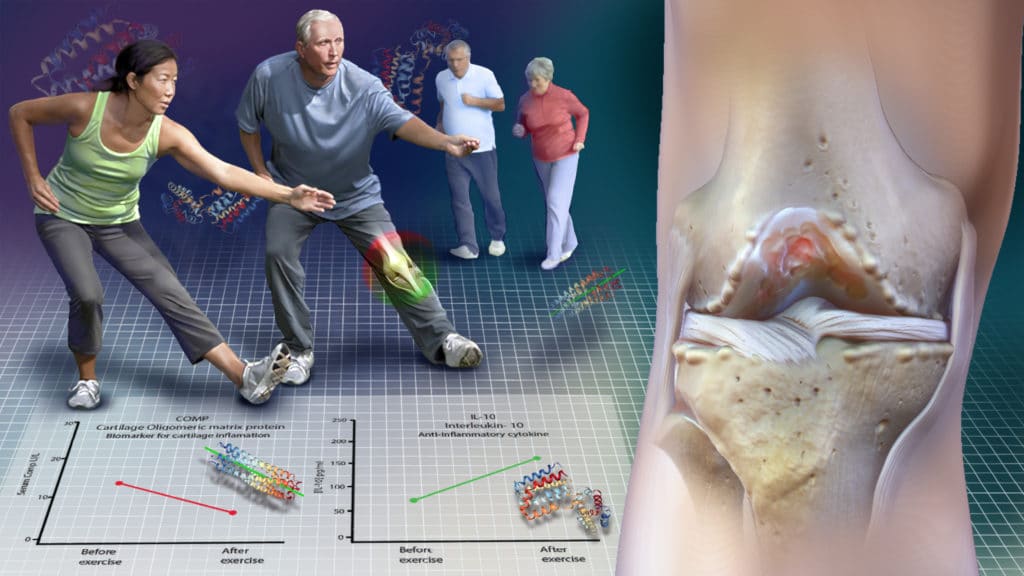

Does Exercise Cause Arthritis?

No, exercise does not cause arthritis. Quite the opposite, runners have a lower incidence of arthritis when compared to a matched group of less active peers. It turns out that your cartilage or the cushioning in your knees thrives on the cyclical loading of running. If you already have osteoarthritis or some degeneration in your knee, then let pain be your guide. It may be best to cross-train with swimming or cycling if your arthritis is advanced enough that running simply hurts too much to pursue.

Can I exercise if I have knee osteoarthritis?

Yes. As a matter of fact, exercise might delay the need for you to think about knee replacement surgery. Weakness in our legs might predispose us to the development of osteoarthritis. Exercise can minimize the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

It’s not like the cartilage or cushioning in your knee is being worn away by moving it. That grinding sound is rarely a sign of something serious going on. More often than not, it is due to inflammation. Osteoarthritis is a complex process. Your overall health, genetics and history of injuries all have a role in determining the fate of your joints. Biology has a lot of impact on the health of our cartilage. That means there are many chemicals in our joints, and some of those chemicals might be harmful to our cartilage. Exercise and even running can decrease the concentration of the nasty chemicals in our joints. This post helps explain the science of why exercise is beneficial to patients who suffer from osteoarthritis.

Is it OK to exercise with pain?

This is a very important issue for the older athlete. Many of you will have discomfort with certain activities. Usually, pain does not imply harm. Sometimes, it does. If you’re concerned, talk to your doctor. More often than not, you do not need to stop exercising. There are no over-use tendon issues that are treated with absolute rest. Our tendons can start to bother us for many reasons, but stopping an exercise program is rarely in your best interest. Stopping your exercises will result in loss of heart health, loss of muscle mass, loss of endurance, and often make it harder to get back into your exercise program.

Aches and pains are commonplace and are often just a mild annoyance or nuisance. Exercise or physiotherapy is often the best way to address them. Again, rest is rarely the right answer. Now, that comes with a caveat. If you think of a pain scale from 0-10, with 0 being no pain; if you have pain during activity and you would rate it under 4 then it is generally ok to continue exercising. By all means, if you have pain that concerns you, then you should stop and see your practitioner.

If you choose to see a doctor, remember to ask if rest is necessary. If they say yes, then ask how long and what the potential downsides of not resting are. For example, groin pain with certain exercises could potentially indicate a stress fracture of the hip. You should not exercise with a stress fracture of your hip. But groin pain can also be due to a muscle strain. As I said before, the best treatment for a muscle strain is to stretch and strengthen it. So do not be afraid to ask your doctor pointed questions about what they believe the source of your pain is, how they are going to prove it, and whether or not continuing to exercise puts you at risk of developing a more serious injury.

In the end, most senior athletes I see do not need to stop their exercises and should not stop their exercises for mild aches and pains. You want to avoid potentially problematic issues like a stress fracture, but you never want the risk of the treatment to be higher than the risk of the injury. So, take it upon yourself to ask what your doctor believes might cause your pain. Have them clarify if any further tests are needed. Ask them if rest is absolutely needed. You will need a solid plan and goal if you aim to continue your exercise pursuits for years to come.

Take-Home Points:

- Exercise is critical to achieving our best possible health.

- Speak with your doctor to be sure you can start an exercise program.

- Know your biomarkers. If something is off, ask what you can do to correct it.

- Age-related muscle loss can be corrected, but it requires resistance exercises.

- Balance training is critical to minimize the risk of falling.

- We do not need to MRI all joint aches and pains.

- Rest is a relative term.

- Respect your body’s need to recover.

- Physical therapy is often effective at treating the pain associated with degenerative tears in your knee, shoulder, hip, and elbow.

- The best exercise is the one you enjoy doing.

Great article! We need a great deal more education and research on sarcopenia if we want a healthy older baby boomer population that doesn’t bankrupt their children!

THanks !! Sarcopenia is an awful process. But it can be managed and reversed — with effort :-)