Most athletes poorly understand a small molecule known as lactate. Lactate is a fuel source for our cells, and we can train to use lactate more efficiently. The brain prefers lactate as fuel. When lactate builds in muscles, the accompanying hydrogen ion (from the breakdown of ATP) changes the pH of the environment, and this is the cause of muscle fatigue. With Zone 2 aerobic training and proper lactate threshold training, we can get to a place where we have more mitochondria to process the lactate, more shuttles to clear the lactate, and build more resilience to elevated lactate levels.

Threshold Training

The term “threshold workout” is thrown around a lot in running circles. But when asked what it means, you’ll quickly find that most runners can’t give you an answer. And those who do can provide wildly different responses.

I’ve heard everything from “a very hard continuous run” to “half-marathon pace” to “something hard, but not too hard.” Chances are you’ve heard one of these descriptions too, and you left the conversation not knowing what they were talking about.

Often, when people say threshold, they are referring to the lactate threshold (LT). But lactate threshold isn’t simply a synonym for hard running – it’s an observable, objective output. And training at it, as part of a polarized training program, can lead to improvements in your fitness and performance.

In this article, we’ll dive into what lactate is, what lactate threshold training is, how to find yours, and how it can be implemented into a polarized training program. Keep in mind… I am not a professional trainer, and I tend to write for runners like me.

Lactate Threshold Workouts in Polarized Training

Too many runners leave their houses every day without a plan. Sure, they might know that they have to do a 5-mile run. But they have no idea how fast it should be, what their optimal heart zone is, or how it should be different from the run they did the day before. We often discussed this when we wrote about the importance of Zone 2 training and Polarized training.

Face it… most runners run too fast on their slow days and too slow on their fast days.

Many blindly follow the “no pain no gain” mantra, assuming that they need to work as hard as possible on every run to see improvement. However, the reality is that this isn’t how runners get build endurance, resilience, power, aerobic capacity, or improve performance. Running too fast too often makes it impossible to recover and can lead to injuries and overtraining.

The world’s top athletes and coaches use a polarized approach in their training. This means that about 80% of their runs end up being easy, “zone 2” runs. Only the remaining 20% is dedicated to hard running.

I’ve talked a lot about zone 2 training, which will dramatically improve your training and health. But the other stuff, the hard 20%, is important too.

Not only is the hard stuff necessary to excel as a runner, but folks with a higher VO2 max also tend to live longer.

Training at your lactate threshold is one of the best uses of your weekly allotment of hard running. In fact, in his book Jack Daniels Running Formula, renowned exercise physiologist Dr. Daniels suggests that over half of your week’s hard running should be done at the lactate threshold. Or in other words, 10% of your weekly mileage should target that zone.

What is the Lactate Threshold?

So what is the lactate threshold? The physiology behind training at this intensity is somewhat complex. To fully understand the lactate threshold, we’ll need to discuss lactate, glycolysis, and how our different muscle types produce energy.

Is Lactate bad for us?

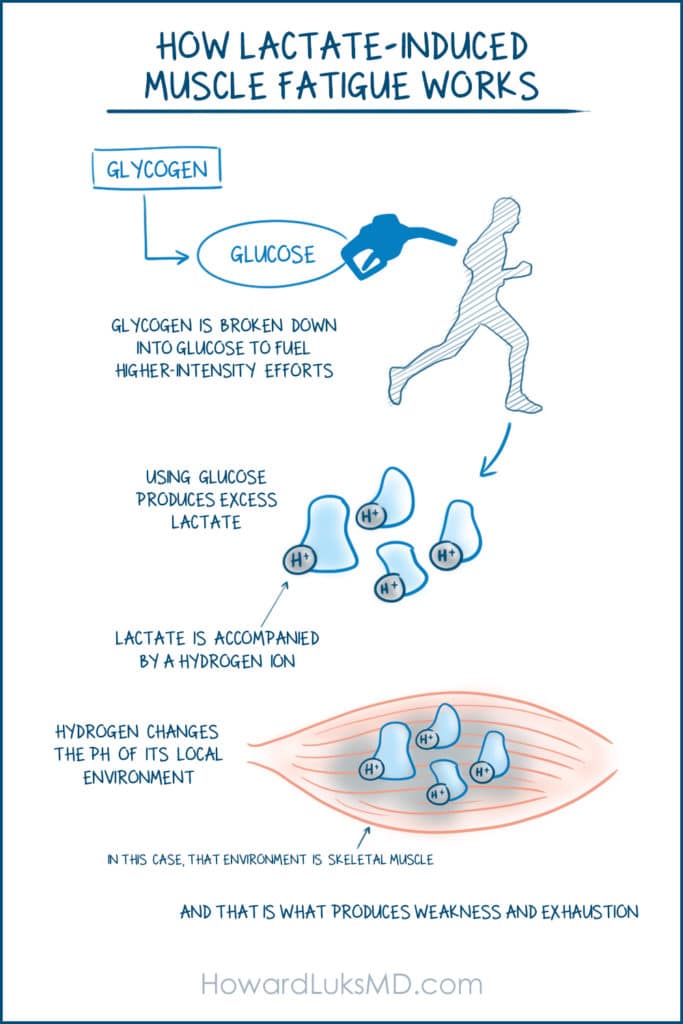

For decades we falsely believed that lactate caused our muscles to fatigue. It was an idea that came from a small sample of studies from the 1950s, and it went unchallenged for decades. We associated a rise in lactate with that burning sensation we felt when we were tired, thinking that the lactate caused our legs to hurt.

However, in the 1980s, Dr. George Brooks led the charge for a different understanding of lactate. He, and eventually other researchers, discovered that lactate isn’t a useless byproduct of energy consumption… it is fuel. Here’s how it works.

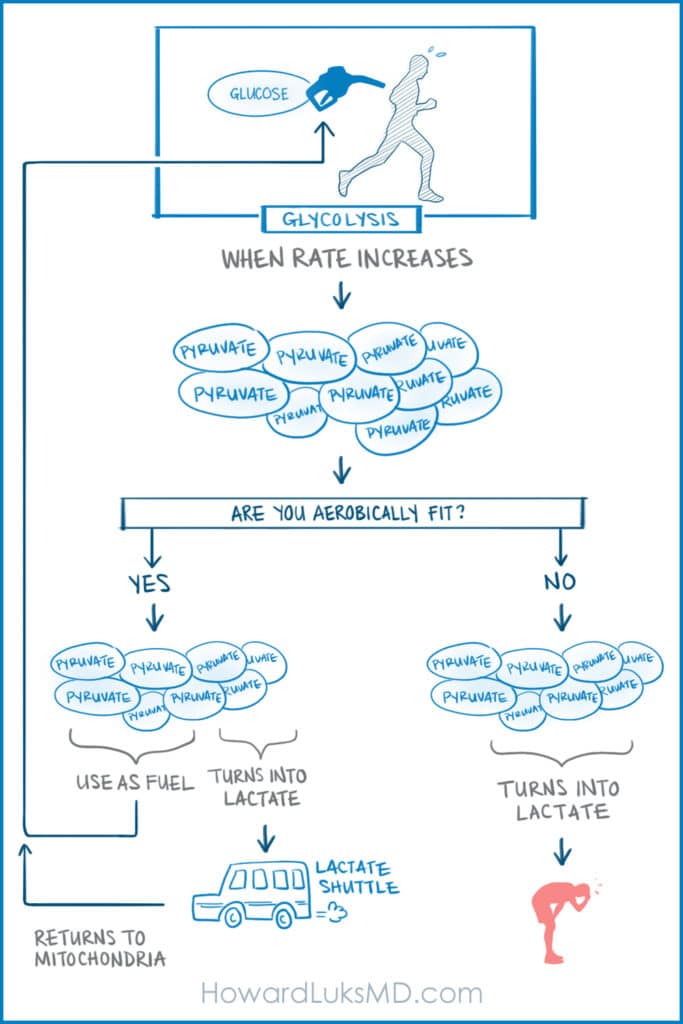

As you might know, when we are running fast, our bodies use glucose to fuel ATP production. This process is called glycolysis. And when glycolysis is performed without oxygen or anaerobically, the byproduct of the process is pyruvate, which can be turned into lactate.

Aerobically fit athletes can use the pyruvate as fuel, thus decreasing the amount that can turn into lactate. Lactate can be returned to the mitochondria in fit individuals via a lactate shuttle, enabling lactate to be utilized as fuel.

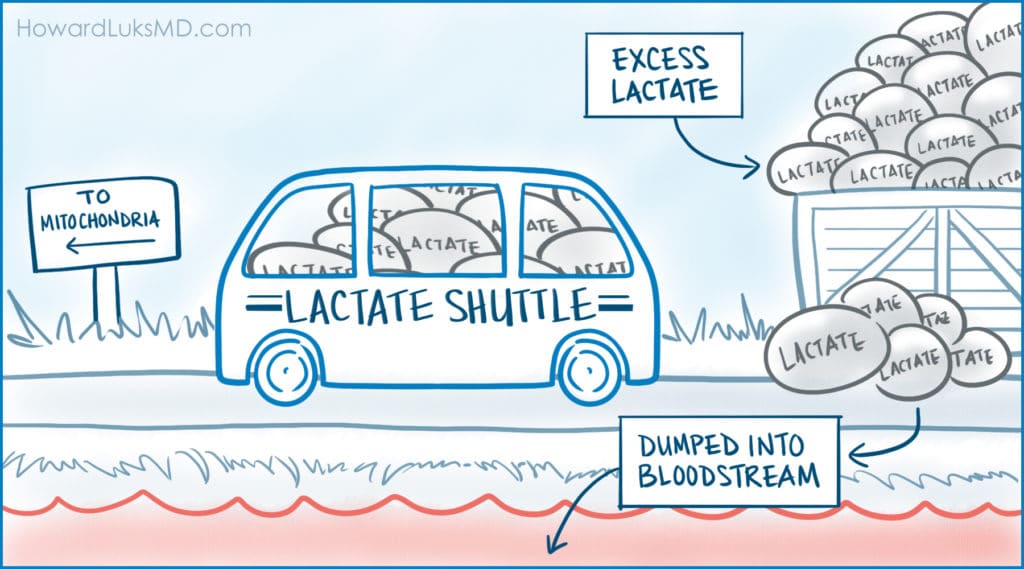

The lactate shuttle: Where champions are made

The more fit we are, the more lactate we can “shuttle” back into the mitochondria to use as fuel. This lactate/pyruvate shuttle plays a role in helping fuel the production of the ATP that powers our muscles when we exercise and mitigates the issues of exhaustion that occur when lactate concentrations are too high. We’ll talk about this later… but it’s not the lactate that causes fatigue, it is an accompanying hydrogen ion from the hydrolysis or breakdown of ATP. That ion makes the environment in the muscle more acidic… and that is one reason why we tire and slow down.

Muscle Fiber Types

All muscle fibers are not created equal. There are several different muscle fibers in our bodies, each of which performs different tasks, has different metabolic functions, and uses energy in different ways.

For the sake of simplicity, we can group all muscle fibers into two categories – fast twitch and slow twitch. And as another broad oversimplification, fast-twitch muscles like to produce energy anaerobically (without oxygen), and slow-twitch muscles like to produce energy aerobically (with oxygen).

In polarized training, when running slowly, we are predominantly using our type 1 or slow-twitch fibers. These type 1 fibers have many mitochondria and can sustain long runs without tiring. However, as our intensity changes, so does the percentage of work being provided by each muscle fiber group. As we increase our effort, we reach a point where all our slow-twitch type 1 fibers are firing. This serves as a signal to recruit our type 2 fast-twitch fibers to meet our load demands.

As we run, the lactate produced by the fast-twitch fibers is released from the muscle cell. From there, our bodies can shuttle that lactate to the mitochondria of the slow-twitch fibers, which use it to fuel their ATP production. That shuttle, however, is not well developed in folks without a solid aerobic base.

What is the lactate threshold?

The lactate threshold is the point at which that “shuttling mechanism” is overstressed. The transport proteins that clear the lactate can’t keep up. If your body cannot shuttle the pyruvate/lactate into your mitochondria fast enough, then the amount of lactate will start to rise. When the excess lactate can’t be returned to the cell, it can’t stay in your muscles, and it is dumped into your bloodstream. At this point, lactate levels increase dramatically, and the lactate threshold has been passed.

So, when we’re training at the lactate threshold, we’re looking to train at a “goldilocks intensity.” We want to train at an effort hard enough to stress the shuttling mechanism appropriately but slow enough to avoid the acidosis of excess lactate in our muscles.

Studies have shown that one of the elite athletes’ biggest advantages is their superior ability to shuttle and repurpose their lactate. By improving our ability to clear lactate, we will eventually sustain faster paces for longer durations.

How to Find Your Lactate Threshold

Methods for identifying your lactate threshold can range from blood lactate monitoring to as simple as “using your best guess.” Here’s some advice on finding your lactate threshold and avoiding pitfalls with less objective methods.

It should be noted… the best and most precise way to identify your Lactate Threshold (LT) is with blood lactate testing. But everyday runners do have other ways to get a reasonably close estimate of our LT.

Don’t rely on your race results

While many people use race results to estimate their lactate threshold, this method has drawbacks.

For example, some coaches suggest that your lactate threshold pace is the same as your “1- hour race pace.” But that doesn’t make very much sense when you think about it. Your lactate levels are going to be higher at the 40-minute mark of that race than, say, the 15- minute mark.

This method also assumes that your body is in the same condition that it was on the day you raced, which is rarely the case. On race day, you ate right, slept well, and tapered your training. On a random workout day, you are coming in less prepared and will likely reach your lactate threshold at a slower pace than on race day.

It’s best to think of the lactate threshold not as a specific pace but as a “state of being” to spend as much time at the correct effort as necessary to create an adaptation.

Methods for Identifying Lactate Threshold

In an ideal world, we would all use a lactate blood monitor. This device can tell us the amount of lactate in our bodies at any time. If you are using one, you should look to find the effort level at which lactate starts to rise very quickly – this is called your onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA.) For many people, this is around 3.5-4mmol of lactate.

For most of us, however, pricking our fingers for blood frequently throughout a workout isn’t very practical.

The good news is that our heart rates are much easier to track during a workout. Heart rate tells us a lot about the states of our bodies, and it can let us know when we are working within the range of our lactate threshold.

Heart rate zones are an appropriate method for everyday runners and folks like me who enjoy running and do not have professional, semi-professional, or podium aspirations :-). For folks who run for a living… blood lactate testing is needed.

The heart rate range for lactate threshold generally correlates to 70-80% of our heart rate reserve. Your heart rate reserve is the difference between your max and resting heart rates.

Let’s assume my max heart rate is 180 BPM and my resting heart rate is 50 BPM. Using the 70-80% range, here’s the formula I would use to determine my heart rate at LT:

.7(180-50) + 50 = 141

.8(180-50) + 50 = 154

So, my HR range for LT is between 141- 154. Once you know your max HR and your resting heart rate, plug them in where I put 180 and 50, respectively. There’s your approximate LT heart rate range.

Another way to approximate your LT is to look back at your data. Your LT will be very close to the HR that you can sustain for an hour on a harder run. You will look at your run and see that you got your HR up to 160+, but eventually, you settled back to 151. You will be able to find that HR that you seem to settle back to… and it’s very likely that this is close to your LT.

How to improve your lactate shuttle.. hint, don’t run faster.

First… and this should be made very clear. The best way to improve your lactate threshold fitness is to build your aerobic base. Not intuitive.. right? By putting in tons of time in Zone 1 and 2, you will build the number of mitochondria and improve their fitness. Without that, you can never develop a well-functioning lactate shuttle.

How To Implement Lactate Threshold in Your Training

We need lactate threshold runs to build our resilience (mental and physical) and ability to maintain that intensity and improve that performance over time. But don’t think that running more at your LT will build your capacity to shuttle lactate and thus enhance your ability to run at your LT for longer. Your LT endurance, via the lactate shuttle, will be built at much lower heart rates. This is the basis for Polarized Training… and this is why the worlds’ top athletes use an 80/20 polarized program.

One common mistake athletes frequently make is assuming that there is one specific way to train their lactate threshold.

The truth is workouts as diverse as track repeats up to a long run can be used to train the LT. Lactate threshold workouts can be executed as either intervals or as a continuous run, depending on factors such as your fitness and the goal of the workout.

Intervals

Interval training also called running repeats, breaks up a continuous workout to include rest (jogging, walking, standing) at specific points in the workout.

There are two primary reasons for breaking a lactate threshold workout into intervals:

- To work at a faster pace than you could sustain on a continuous run

- To ensure that your heart rate doesn’t drift into too high of a zone

Here are some examples of runners who could benefit from each category:

Lactate Threshold for a Faster Pace:

Let’s use my runner from earlier (with the LT heart rate range of 141-154), and assume this athlete is training for a 5k.

When attempting continuous runs to train their LT, anytime they start running their 5k pace; their heart rate shoots above 154 after just 3 minutes. So, they have to use LT intervals to target the pace they are trying to train at.

This athlete could use a workout such as:

10 x 2 minutes @ LT range (141-154) with a 1-minute walk in between.

Because the 2 minute intervals are short, it might require a faster pace to reach LT heart range. The 1-minute walk in between allows their heart rate to recover.

This type of workout can be changed to fit the runner’s individual needs. Some runners might be able to handle longer reps at a faster pace, and others might need longer rests to ensure that they are staying within the bounds of their lactate threshold.

Lactate interval training is a favorite of coaches and athletes worldwide. It gives you all of the benefits of training within your lactate threshold range, while still allowing you to train at faster paces.

Lactate Threshold to Avoid Cardiac Drift:

One problem with new runners is that they can’t spend much time in their lactate threshold range before exceeding it. This is because their lactate shuttling mechanisms aren’t very developed, and more often than not, they have very poor aerobic endurance.

When attempting a continuous LT run, the athlete we used as an example above might find themselves at 141 bpm 3 minutes into the run, and without changing their pace, they are suddenly at 157 just two minutes later. Even on longer, slower runs, you may find that your HR increases despite no change in pace or elevation. This is referred to as cardiac drift. This is a signal that you are not aerobically fit for this distance—The answer to building that capacity… more zone 2, not more fast intervals.

For athletes who want to train their LT but don’t have a strong enough aerobic base, intervals are often the best way for new runners to train their lactate thresholds. Here’s a recommendation on how I would structure a workout for my sample athlete above:

Run at a pace that puts them at around 141 bpm within 90 seconds

Keep the pace as steady as possible until they hit 154 bpm

Immediately after their HR hits 154, they walk until their heart rate has recovered to 120 bpm

Repeat this cycle until they’ve run anywhere between 10-20 minutes in their LT range.

Once this workout has been completed a few times, athletes should notice that the amount of time they can spend in their LT range has improved significantly.

Steady-state runs and progressions are two styles of workouts that can effectively train the LT.

Steady State

Steady-state runs are typically between 15-25 minutes. The point of these runs is fairly simple – spend the entire duration of the run in the lactate threshold range.

Athletes performing steady-state runs must be fit enough to make sure that they can complete the entire run in the LT range. Drifting outside the upper limit can negatively impact the intended effect of the workout, lengthen their recovery, risk overtraining, and increase the risk of injury.

Progressions

Very few athletes can run in their lactate threshold zone for a full 60 minutes. But, athletes can work LT training into a longer run by running progressively faster throughout the workout.

In a well-executed progression, an athlete will start in zone 1 or 2 and work up to the point where they are running in their LT zone by the end of the run.

It’s essential not to focus on your pace when running a progression. Because of the fatigue you will accrue from the first portion of the workout— you will almost certainly reach your LT range at a slower pace than if you were running it fresh.

The point of a progression is to teach your body how to clear lactate even in a state of fatigue. Progressions are often anywhere between 20-60 minutes.

Lactate Threshold Training Can Take You to New Heights

If there’s one thing you remember from the article, let it be this: lactate is not your enemy. There’s another super important take-home is: Build your aerobic base!! That means many hours of low-intensity zone 2 training. This will build your mitochondrial/metabolic physiology to enable you to clear lactate and process it.

Elite runners don’t produce less lactic acid than the average runner. They are just better at clearing it and repurposing it for its intended purpose as fuel.

So the next time you go out for a hard run, consider being a little more intentional about the purpose of your workout. Training within the range of your lactate threshold can improve your ability to clear lactic acid, and your improvement from these types of workouts might surprise you.

Thanks for another great article! I’m confused by one thing. My resting heart rate is 45 and max is about 175. This gives me an lower LT of .7(175-45) + 45 = 136. I.e. my LT range is 5 beats lower than your example even though the difference between my max and resting rates is the same. My intuition would be that someone with a lower resting heart rate is more fit and should have a higher LT range. Note that even if my max rate were the same at 180, my LT range would still be lower (139.5 vs. 141) because of my lower resting heart rate.

Does this make sense, or am I over-analyzing a rough guideline? Thanks.

Hi…

Using that formula provides us with a rough, but a decent estimate of our LT. Well-trained, coached, and elite athletes will be tested to see exactly where their LT1 and LT2 (AeT and LT) are. If you are tracking your HRs on Strava, Training Peaks, etc… skim through your faster (and longer) LT runs and see where the HR is that you tend to settle into. After a few months of observation, it is pretty easy to spot on runs longer than 30-45 min or rides longer than 60-90 minutes. I believe you might find it is very close to this estimate. Plus, your LT will change often… based on your recovery, load, stress, sleep, and so on.

Hi,

A very approachable article with some good information but please hold back on the endurance dogma. The OBLA of 4.0 mmol.L-1 has been shown to overestimate MLSS. And even the original authors that suggested it have cautioned the use of this OBLA method, given the lack of a significant correlation. Also, regarding the 70-80% of heart rate reserve, no research has directly investigated the reliability of determining exercise intensities via this method. As an alternative, there is evidence to support the validity of Critical Power and Critical Speed to separate the heavy and severe domains of exercise.

Thanks Ed…Endurance is my middle name… and at this stage of my very average career mostly what I focus on. :-)

Hi Howard. Very interesting article.

From a physiological viewpoint, if I feel muscle “burn” on 5min intervals…am I at LT or have I gone too far and need to use less intensity?

Hello Howard and thank you for the interesting article! I very much agree on the well established polarized training model, but being a time-crunched athlete with two small boys I have a question. If recovery is not an issue (this means that performance on the high intensity sessions will not be compromised), do we lose some adaptations if going too hard? Say for example if we would do a linear progression run of 60 minutes from around 2.0 to 3.0 lactate instead of doing it 1.2 to 2.0? Thank you in advance.

Hi… well, it is an issue. Because most of our training.. 80-90%, should be at or just below our LT1 (2mmol/L). When you rise above that, your physiology changes. Your mitochondria and cells switch to more glycolysis and you’re not building your aerobic base… you’re stressing yourself unnecessarily. We cover this in our lactate threshold post and our zone 2 post.