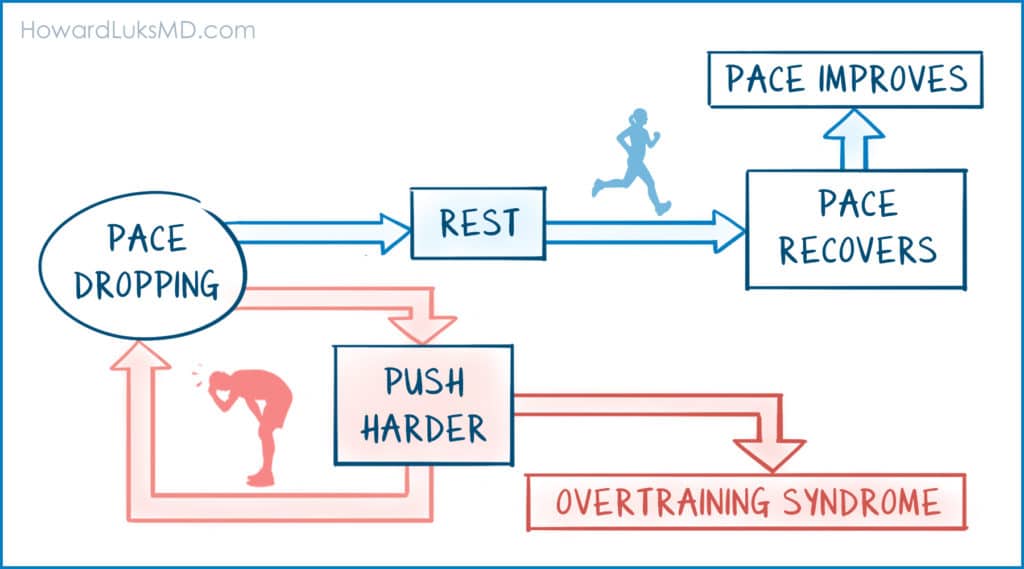

Most runners run too fast on their slow days and too slow on their fast days. Most runners/cyclists are not adept at understanding load management. Instead of resting, we often push harder if we see our pace dropping, or time/mile increasing. This can be a trap and lead to overreaching and worse, overtraining.

While we all know that aerobic exercise helps us live our best lives, there are dangers associated with doing too much too fast. There are dangers to aerobic athletes that train too often, too quickly, and do not recognize the need for recovery. Those dangers are especially potent at certain times of the year when our training enthusiasm is often at its highest.

Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) can be detrimental to an athlete’s performance, health, and emotional state, and runners oftentimes don’t realize it’s happening until it’s too late. Overtraining is a late manifestation of training too hard for too long… and it can end or seriously delay a runner’s career.

More Isn’t Always Better

Here’s a story I’ve seen time and time again.

A runner, let’s call her Jill, gets serious about her goals. Jill decides this is the year she is really going to focus on her training. She’s going to stop skipping runs. She is going to run more mileage and harder workouts than ever before.

3 weeks into the year she finishes the longest and fastest training run of her life. The rest of the afternoon she can barely get up to walk to the bathroom, but hey “that’s just part of hard training, right?”

A few days later she is back on the track for some speed intervals. She runs 400m repeats until her head is spinning.

The next morning the alarm goes off and running is the last thing Jill wants to do. She has throbbing pain in her foot, she only slept 5 hours, and she barely has the energy to get out of bed – let alone do that 6-mile run she had planned.

But she tells herself she has to get it done, so she slogs through another miserable run.

This process repeats itself in the weeks leading up to her big race. Running has slowly shifted from being a highlight of her day to a chore. She barely has the energy to finish her runs.

But she tells herself it will all be worth it when she crosses the line and sees that new personal best.

Race day finally comes. The gun goes off, and right away something is wrong. Jill feels like she’s running through mud. She can’t catch her breath. Does she dare look at her watch? Her typical heart rate for this pace is 155, but today she’s at 167.

She looks down and can’t believe what it says. She’s running 20 seconds per mile slower than her goal! Her aching legs barely cross the finish line; her time is the slowest she’s run in years.

Jill can’t believe it. How could this happen? This was the hardest she had trained in her whole life– how did she run slower than ever?

Rest and recovery to reduce the risk of overtraining

Recovery can be a weapon… and lack of rest/recovery time can be a recipe for disaster.

Many cases of overtraining are actually cases of under-recovering.

If that story sounds familiar, it’s because 35% of runners will experience Overtraining Syndrome at some point. We know that up to a certain point an increased training load helps us improve as athletes. But why is it that eventually things switch, and more training actually hurts our health and performances?

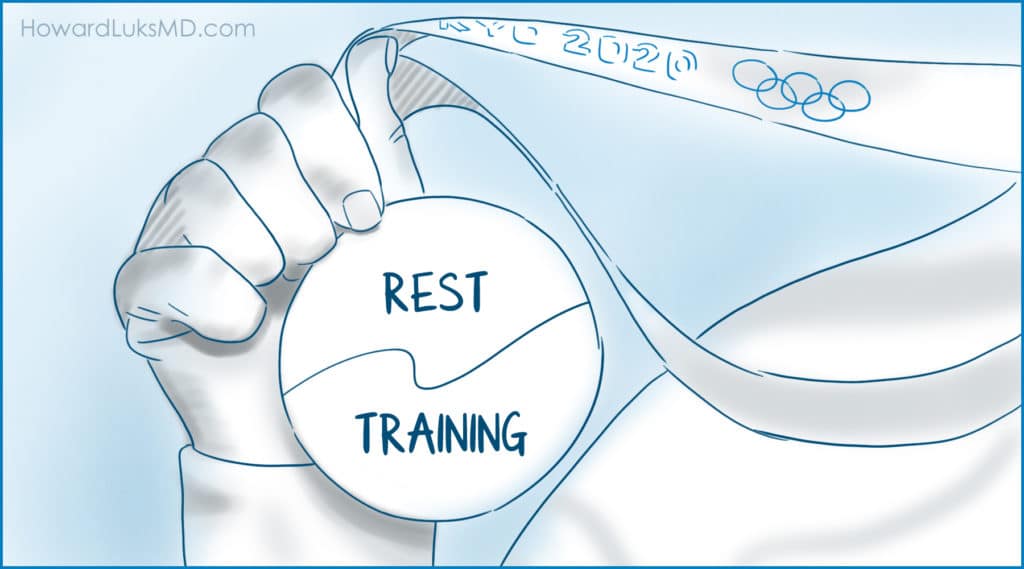

Prominent exercise physiologist and professional coach Steve Magness has a simple answer. He has spent much of his career studying athletic performance, and in his book Peak Performance, he offers a pretty straightforward equation: Stress + Rest = Adaptation.

The problem is, that formula is out of balance for a lot of runners. They love the stress but don’t realize that rest is just as important to their improvement. They treat rest as something that just happens between runs, not a variable they need to actively prioritize to get better.

Taking more preventative days off, spending more of our time at lower training intensities, cross-training, and improving our diets and sleep are ways we can be more intentional with rest in our training.

Overtraining Advice From an Olympian

Olympic bronze medalist Molly Seidel has talked about the critical role rest has played in her improvement.

Molly was a great runner in college who got stuck in a cycle of injuries and disappointing results in her post-collegiate years. In 2018, she seriously considered retiring from professional running.

In 2020, however, she won the US Olympic Marathon Trials, and in 2021 shocked the world with a bronze medal finish at the Tokyo Olympic Marathon. Molly has talked extensively about how her shift to focusing more on her recovery, and less on her actual running, has been the single most important factor in her ascension to the world-class level.

She has even suggested that it’s the reason why so many incredible athletes come from Kenya. While many people theorize that it’s their workouts, diet, or genetics, Seidel says she believes that Kenyan athletes are great because they know what it really means to recover. While rest does play a critical role, so does proper training. The concept of running slow to run fast is how most elite athletes are trained. We dove into the importance of these slower, zone 2 runs in this article.

If taking an off day and running slower on easy runs helped Molly Seidel podium at the Olympics, it can definitely help you train optimally, run faster, and live better.

How to Know If You are Overtraining

So how do we know where the overtraining line is? Here are three science-backed ways you can monitor your training load.

1. Heart Rate and HRV to Monitor for Overtraining

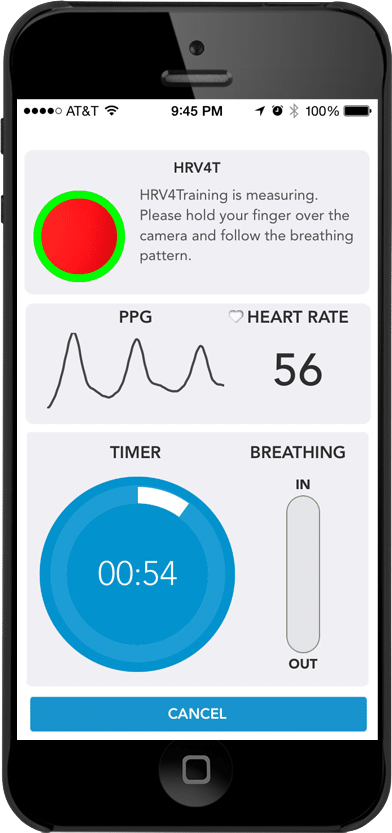

Heart rate tells us a lot about the state of our bodies. While heart rate is often used to gauge the intensity of our training, paying attention to its day-to-day changes can give us important insights into our recovery levels.

For example, if your beats per minute (BPM) is 150 on a run on one day, and, under identical conditions, at 165 bpm the next day, we can reasonably assume that you are less recovered on the second day than the first. That would be a signal to stop and walk– something aerobic athletes are not good at recognizing.

Monitoring your morning resting heart rate is just as important. If your resting heart rate is 48 and you wake up the next day and it’s 54 then you should not plan on doing any training sessions.

Do you have questions regarding an Orthopedic injury or longevity?

Do you want to talk to an expert who can listen to you for 45-60 minutes and explain the options in detail?

Dr. Howard Luks offers remote guidance sessions to review your X-ray or MRI images and explain your options.

Dr. Luks has also received hundreds of requests for educational sessions on the topics discussed in his book, Longevity Simplified.

And BPM isn’t the only metric important for tracking recovery. Heart rate variability (HRV) is actually a more important number for understanding your body’s recovery timetable. HRV is the measure of how consistent your heart is beating from one beat to the next. An inconsistent heartbeat (high HRV) actually suggests that you’re ready to go; when there is little variability (low HRV) it’s a sign that your body still needs recovery.

When the heart rate data tells you you need more recovery time, it’s probably a good idea to run very easily, opt for a walk, or even take the day completely off. Adapting your training to your body, instead of following a predetermined plan, is the best way to ensure that you are getting enough rest to reap positive training adaptations.

The goal with monitoring your heart rate, and HRV is to achieve a morning steady state. You want to avoid training that produces wide fluctuations in your morning HRV or resting heart rate.

2. Mood Fluctuation and Overtraining

Overtraining Syndrome affects more than just your physical health – your emotional health is at stake too.

If you are noticing a shift in your attitude towards running from “I love this” to “Oh, I have to run again”, chances are you’re slipping into OTS territory.

And this isn’t just anecdotal advice; it’s based on science. One study showed that by having swimmers fill out a psychological questionnaire before their workout, and adjusting their training intensity based on how they were feeling, they were able to reduce their rate of overtraining to nearly 0%.

3. Perceived Exertion at Training Paces

Athletes who are overtrained often report difficulty in running paces that used to feel easy for them.

It’s important to be clear that a few tough runs here and there don’t necessarily mean that you’re overtraining. There are days that your normal training pace is going to feel more difficult than other days, and that’s ok.

The problem is when it becomes a pattern. If you notice that those runs that used to energize you are leaving you feeling drained, or you are constantly dropping out or having to adjust the paces on your workouts, then chances are you are starting to overtrain.

Avoid Overtraining for Optimal Results

Paying attention to the signs our bodies are giving us is the best way to avoid the dangers of overtraining.

By continuing to be intentional about our rest, monitoring our fatigue levels, and having the confidence to back off our training when things are too much, we can train in a way that is optimal for our physical health and athletic performance.

Let’s all challenge ourselves to live better, perform better, adapt better, and train better by training properly, and allowing ourselves to recover and rest.

Laura

Question: When I am feeling run down, my HR tends to be lower than normal for same type of exercise or even for the day. Is this normal? Thanks!

That can be a sign that your parasympathetic nervous system is on overdrive. That is often a sign to take a rest day. Track and monitor your HRV… that will help you understand the effects that your exercise is having on your body as a whole.