The treatment of meniscus tears is far more nuanced and complicated than you think.

Meniscus tears are one of the most common knee issues, often leading to a cascade of nuanced decisions regarding the best course of treatment. For decades, the prevailing approach had been surgical intervention, primarily through procedures like meniscectomy (removal of the torn meniscus). However, emerging evidence from numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggests that routine surgery may not always be the best option. Furthermore, when surgery is considered, far more tears are repairable than we initially thought. As we delve into the intricacies of meniscus tears, we must highlight when surgery is necessary, when non-surgical treatment suffices, and the potential biases that may influence surgical decisions.

The Anatomy and Function of the Meniscus

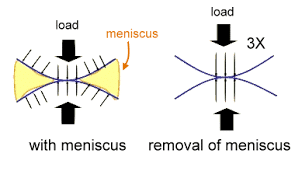

The meniscus is a C-shaped cartilage in the knee that acts as a cushion between the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (shin bone). Each knee has two menisci—the medial (inside) and the lateral (outside). The menisci are crucial in load distribution, shock absorption, and joint stability.

One of the critical functions of the meniscus is to manage hoop stresses, which are the circumferential tensile forces generated when the knee bears weight. As the knee undergoes loading, the menisci deform slightly, spreading the load more evenly across the knee joint. This deformation helps convert compressive forces into tensile forces along the circumferential fibers of the meniscus, effectively distributing the load and protecting the underlying articular cartilage from excessive stress and potential damage. By mitigating these forces, the menisci helps prevent cartilage wear and contributes to the longevity of the knee joint.

The Prevalence of Meniscus Surgery

For years, meniscus tears have often led to surgical intervention, particularly partial meniscectomy. However, recent studies have questioned the necessity of such procedures in many cases. Let’s explore some major randomized controlled trials that have shaped our understanding.

Major Randomized Controlled Trials on Meniscus Tears

MeTeOR Trial (Meniscal Tear in Osteoarthritis Research)

- This landmark study compared physical therapy (PT) to arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) in patients with meniscus tears and osteoarthritis. The results showed no significant difference in functional improvement between the two groups after 6 and 12 months. The conclusion was clear: PT was non-inferior to APM for meniscus tears in the presence of knee osteoarthritis.

Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study

- Conducted in Finland, this RCT involved patients with degenerative meniscal tears. Participants were randomized to receive either APM or sham surgery (placebo). After 12 months, both groups showed similar improvements in knee function and pain relief, indicating that APM provided no additional benefit over placebo.

ESCAPE Study

- This Dutch study focused on middle-aged patients with meniscal tears. Participants were assigned to either early surgery or a structured exercise program. After two years, there was no significant difference in knee function or pain levels between the two groups. Again, exercise therapy was found to be as effective as surgery.

Drawbacks of Meniscus Tear Studies

While these major RCTs have significantly advanced our understanding, they also come with certain limitations that should be considered:

- Patient Selection and Exclusion Criteria

- Many studies limit participation to specific populations, such as those with degenerative meniscal tears or those with coexisting osteoarthritis. This selective inclusion can result in findings that may not be generalizable to all patients with meniscus tears. For instance, younger patients with traumatic tears or athletes with acute injuries may not be well-represented in these studies.

- Nature of Meniscus Tears

- The studies often focus on degenerative tears rather than traumatic tears, which can present differently in terms of symptoms and treatment outcomes. Traumatic tears, often resulting from sports injuries, may require different management strategies compared to degenerative tears that occur due to aging.

- Short-Term Follow-Up

- Many trials have relatively short follow-up periods (e.g., six months to 2 years). While they provide valuable data on short-term outcomes, the long-term effects of non-surgical treatment versus surgery are less well-documented. Longer follow-up is needed to fully understand the implications of both treatment approaches on knee health over time.

- Placebo Effect

- In studies like the Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study, where sham surgery was used, the placebo effect can play a significant role. Patients who believe they have undergone surgery might report improvements due to psychological factors rather than the actual efficacy of the intervention.

- Exercise Program Adherence

- The effectiveness of physical therapy and exercise programs relies heavily on patient adherence. In real-world settings, not all patients may be as compliant as those in controlled trial environments, potentially affecting the generalizability of the results. Sadly, it often takes surgical intervention for people to adhere to a rehabilitation regimen. Human psychology is funny like that.

- Variability in Surgical Techniques

- There can be significant variability in surgical techniques and the skill of the surgeons performing the procedures. This variability can influence outcomes and may not be fully accounted for in the study designs.

Are Degenerative Meniscal Changes Age-Appropriate Findings?

It is essential to distinguish between traumatic meniscus tears and degenerative changes. Many degenerative meniscal changes are age-appropriate findings and do not necessarily imply injury. The term “tear” suggests an acute or traumatic event, whereas degenerative changes are often a natural part of aging and may not require intervention.

As people age, the menisci, like other joint structures, undergo changes associated with aging. These changes can be detected on MRI and may be labeled as tears. However, in the absence of significant trauma or acute symptoms, these degenerative changes often do not require treatment and can be managed non-operatively. It’s crucial to avoid over-treating these age-appropriate findings, as many individuals remain asymptomatic and highly functional despite the presence of degenerative meniscal changes.

When Surgery May Be Necessary

While non-surgical treatments like physical therapy are often effective, there are instances where surgery may be the best option. Specific types of meniscus tears, such as flap tears, can cause mechanical symptoms like locking or catching in the knee. These symptoms occur when a piece of the torn meniscus interferes with the knee’s movement, causing pain and functional limitations. In such cases, surgical intervention to remove or repair the torn piece can provide significant relief and improve knee function. The same can be said for many root tears and bucket handle tears.

The Ethical Quandary in Meniscus Surgery

Orthopedic surgeons often face a dilemma: whether to repair or remove the torn meniscus. Interestingly, the compensation for both procedures is typically the same, which may inadvertently influence the decision-making process. Although never conclusively proven, financial incentives could potentially sway some surgeons towards meniscectomy, given its historically higher frequency and perceived simplicity compared to repair.

Advances in Meniscus Repair

The approach to meniscus tears has evolved significantly. Tears once deemed irreparable are now successfully repaired, thanks to advancements in surgical techniques and a better understanding of meniscus healing. Modern repair techniques offer promising outcomes, particularly in preserving meniscal tissue and maintaining knee health.

Do you have questions regarding an Orthopedic injury or longevity?

Do you want to talk to an expert who can listen to you for 45-60 minutes and explain the options in detail?

Dr. Howard Luks offers remote guidance sessions to review your X-ray or MRI images and explain your options.

Dr. Luks has also received hundreds of requests for educational sessions on the topics discussed in his book, Longevity Simplified.

Meniscus repair is especially beneficial for preserving knee function. Removal of a portion of the meniscus almost universally results in arthritic changes. This is particularly true on the lateral or outer side of the knee. Repairing the meniscus rather than removing it helps protect the knee from degenerative changes and preserves its shock-absorbing function.

Conclusion: Balancing Surgery and Conservative Treatment

The treatment of meniscus tears requires a nuanced approach. The evidence from RCTs strongly supports the efficacy of physical therapy and exercise programs as non-inferior alternatives to surgery for many patients. However, certain tear types and individual patient circumstances may necessitate surgical intervention.

Patients should engage in informed discussions with their orthopedic surgeons, considering the nature of their meniscus tear and the available evidence on treatment outcomes. Ultimately, the goal is to tailor the treatment plan to the patient’s needs, ensuring the best possible outcome for knee function and overall quality of life.